Finding DNA Subsequences with Knuth-Morris-Pratt

Substring searching has become so ubiquitous in recent years that it’s easy to take for granted the beauty and ingenuity of automata-based pattern matching. Remarkably, the importance of these algorithms has, if anything, continued to grow. Knuth-Morris-Pratt (KMP) was published in 1974 but Skiena’s ‘killer applications’ for string processing — online search and computational biology — wouldn’t emerge until decades later.

The key insight behind KMP is that it’s never necessary to backtrack when searching the text. Examining each character once is enough. Consequently the algorithmic complexity is reduced from O(mn) in the naïve case to O(m+n). KMP achieves this by re-framing the problem. Rather than whether a substring exists, it asks: what currently is the longest prefix of the pattern that is also a suffix of the input string? Substrings can then be detected by checking whether the prefix length is equal to the pattern length.

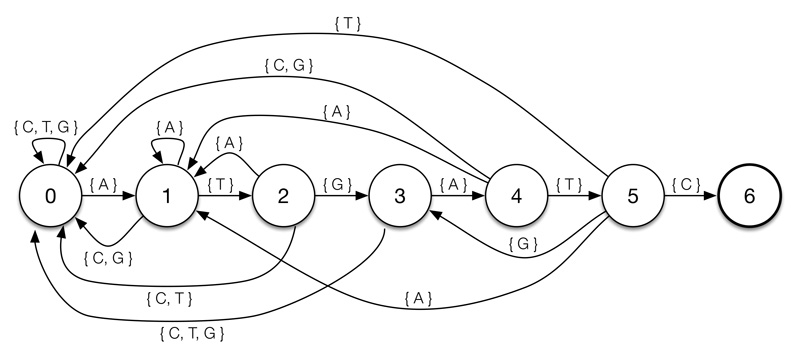

A DFA representing the pattern ‘ATGATC’. States indicate partial matches so, for example, being in state two indicates that the last two characters were ‘AT’.

A DFA representing the pattern ‘ATGATC’. States indicate partial matches so, for example, being in state two indicates that the last two characters were ‘AT’.

The longest prefix is tracked in a deterministic finite automaton (DFA), created by pre-processing the pattern. Each state represents a particular partial match and the transition arrows indicate effect of new characters on the size of the match.

Creating the DFA

Most of the code for creating the DFA is straightforward. The one non-obvious step is calculating mismatch transitions. Logically, when a mismatch occurs we want to shift the index one character to the right and start again. This would mean resetting the DFA and giving it the string pattern[1:state] (since the pattern is matched against itself in the pre-processing stage, it is the text). Doing this for each mismatch calculation would be expensive so instead we maintain a variable x, which is always the result of running the pattern ‘shifted one position over’ through the DFA.def create_dfa(pattern, alphabet):

# create an empty transition table of states and letters

dfa = [dict((i, 0) for i in alphabet) for j in pattern]

dfa[0][pattern[0]] = 1 # initial transition

x = 0 # initial state

for state in xrange(1, len(dfa)):

# match transition

dfa[state][pattern[state]] = state + 1

# copy mismatch transitions

for l in alphabet:

dfa[state][l] = dfa[x][l]

# update restart state

x = dfa[x][pattern[state]]

return dfa

Once the DFA is constructed the rest is fairly trivial.def kmp(needle, haystack, alphabet):

dfa = create_dfa(needle, alphabet)

x = 0

for index, character in enumerate(haystack):

x = dfa[x][character]

if x == len(needle):

return index

return False

Note that this function doesn’t quite hit the O(m+n) target as it’s also proportional alphabet size and therefore O(m|Σ| + n). But this won’t be a significant problem for small alphabets like DNA. The code here implements Sedgwick and Wayne’s take on KMP. The original paper uses a more sophisticated algorithm to create a non-deterministic finite automaton and thereby avoid scaling with |Σ|.

Searching Human DNA

The reasons for using human DNA as a test dataset go beyond its conveniently small alphabet size. Identifying whether a given genetic sequence occurs elsewhere is a question frequently asked by molecular biologists and, at over three billion basepairs, having an efficient algorithm for doing so is an essential prerequisite for any kind of large scale analysis.

The human genome can be downloaded here. You’ll also need a twobitreader to parse it. Even a single chromosome can take up a lot of memory so the code below processes it in chunks of one million nucleotides. Since KMP doesn’t backtrack, each nucleotide can be read once and thrown away.def chromosone(number, buffer_size=1000000):

genome = twobitreader.TwoBitFile('hg38.2bit')

chromosome = genome['chr%d' % number]

for i in xrange(0, len(chromosome), buffer_size):

buffer = chromosone[:i]

for nucleotide in buffer:

yield nucleotide.lower()

Then it’s just a matter of giving KMP a pattern, chromosome and alphabet.kmp('atgatc', chromosone(20), 'atgcn')

The result can be verified with Ensembl, quite literally a search engine for humans. It can also be modified to match multiple patterns by creating a list of DFAs and processing them all at once. Indeed, the Aho–Corasick algorithm takes this a step further and combines multiple patterns into a single DFA!