Counting Calories: How We Improved the Performance and Developer Experience of UberEats.com

I originally wrote this article for the Uber engineering blog.

At Uber Eats, we want ordering the food you crave at the touch of a button to be as easy as possible, whether on desktop or mobile. That’s why our engineering team spends a lot of time thinking about, building, and maintaining web applications for restaurants and customers. Uber Eats relies heavily on web-based applications, from our Restaurants app (which targets the web through React Native for Web) to our extensive analytics platform and menu tooling.

UberEats.com, which lets eaters order food through a web interface, complements our mobile applications by filling niches in which a web app provides a better user experience. For example, the extra screen real estate makes it easier to place large orders.

It also gives us the flexibility to integrate the Uber Eats food ordering experience with other Uber apps, providing a more seamless experience and freeing up native storage space on user’s phones. With newer versions of the Uber Rider app, for instance, users can order food directly in the same interface without having to install the Uber Eats app. A WebView version of UberEats.com makes this functionality possible.

The UberEats.com team spent the last year re-writing the web app from the ground up to make it more performant and easier to use. While refining UberEats.com, we prioritized increasing developer productivity without compromising on quality or stability.

As many engineers know, however, rewrites are not a panacea; they can be expensive, time-consuming endeavors. When planning a rewrite it’s easy to underestimate the scope of the task at hand, setting the project up for failure. In spite of the risks, building a new system from scratch tends to be much more alluring than revising an existing one because it provides an opportunity to re-think the existing architecture from scratch and address any structural pain points. Despite these benefits, working with an existing system is safer: engineers typically understand the current implementation and can accurately forecast the complexity of any migration project immediately.

Keeping this in mind, we considered numerous factors in deciding whether or not to rewrite UberEats.com. Ultimately, we decided that a rewrite would enable us to both conserve time and resources as well as implement new and intuitive features. This decision led to a more performant and scalable platform that facilitated an improved user experience for users of the web app.

A saga of Sagas

Written in JavaScript, UberEats.com was launched in early 2016 as a React single-page web app that leveraged Redux/Redux-Saga for state management and a backend powered by Express, a popular Node.JS HTTP server. Custom code allowed for the React components to be rendered on the server. However, the use of a Saga pattern led to additional complexity that prevented the web app from scaling to meet user needs and keep up with developer velocity.

UberEats.com used Redux-Saga for asynchronous actions such as data fetching. Sagas in this context are very different from the Saga pattern, introduced in the 1987 white paper, Sagas, by Hector Garcia-Molina and Kenneth Salem, to improve the performance of long-lived transactions. Instead, Redux-Sagas behave like microservices, communicating using “effects,” which have a type and payload.

Effects can read state from the Redux store, wait on promises, and listen for specific Redux actions. An effect that fetched user information from our backend might look like:

{

CALL: {

fn: fetchUserInformation, // a function that returns a promise

args: [1] // the ID of the user

}

}

Sagas are particularly useful for orchestrating long-running asynchronous tasks. For example, one Saga could periodically call an HTTP endpoint for information on in-progress orders, while another Saga could listen for updates and display a notification, as depicted below:

function fetchOrdersSaga() {

while (true) {

// Call an HTTP endpoint

try {

const orders = yield call(fetchOrders);

yield put(fetchOrdersSuccess(orders);

} catch (err) {

yield put(fetchOrdersFailure(err));

}

// wait 5s

yield call(delay, 5000);

}

}

function notifyUserSaga() {

// Wait until we have the necessary permissions

const enabled = yield call(getNotificationsPermission());

if (!enabled) {

return;

}

while (true) {

// Wait for an update to the orders store

const orders = yield take(ORDERS_UPDATE);

// Notify the user if something interesting has happened

if (isFoodArriving(orders)) {

yield put(foodArrivingNotification(orders))

}

}

}

Over time, engineers came to rely heavily on Sagas for day-to-day feature development. This dependency on Sagas gave rise to a pattern of “UI Sagas,” or Sagas that existed just to load the data necessary to render a specific component. For example, our Restaurant Categories page had a Saga that asserted a valid category existed and fetched the relevant stores for that category. Our data layer consisted of well over 100 Sagas spread across 68 different reducers, and over half of these were “UI Sagas.”

As the number of Sagas–and interdependencies between Sagas–increased, maintenance of the codebase and feature development became slower. Refactoring code was error-prone because it was difficult to determine which Sagas were needed for a particular page or feature to work properly. Sagas might implicitly rely on other Sagas having been run already, but the abstraction itself doesn’t provide a way of statically validating these dependencies. An engineer refactoring a Saga in one part of the app might inadvertently break another part of the app. For example, nine Sagas were listening and reacting to the USER_ADDRESS_LOADED event. Changing the address entry flow required an engineer to track down how each Saga was using the event and ensure that it would continue to function properly. An address is a pretty important piece of information in the food delivery business and, invariably, bugs were introduced that resulted in hungry users.

Making use of existing state could also be difficult. Adding new features might involve tracing through dozens of files to determine where a particular field was being populated. The user’s state (nearby restaurants, orders, etc.) was fetched and normalized into different Redux stores. Memoized functions that read and adapted state from the Redux store, while useful for improving performance, added an additional layer of complexity.

Aside from slowing down maintenance and feature development, the inability to statically reason about Saga interdependencies made it difficult to safely code split the application. Code splitting aims to improve performance by splitting application code into different bundles to try and minimize the amount of code sent to the browser.

We used Webpack and the dynamic imports syntax for code splitting. Dynamic imports work similarly to regular JavaScript imports, except that instead of returning a reference to the imported code you get a promise which resolves to the imported code. This allows us to express that something might be a dependency based on what branches in the code are ultimately followed. Webpack uses static analysis to identify possible execution paths and group our codebase into different bundles. To maximize the benefits of code splitting, engineers need a very modular codebase; a single chain of regular imports will prevent Webpack from generating reasonably-sized bundles.

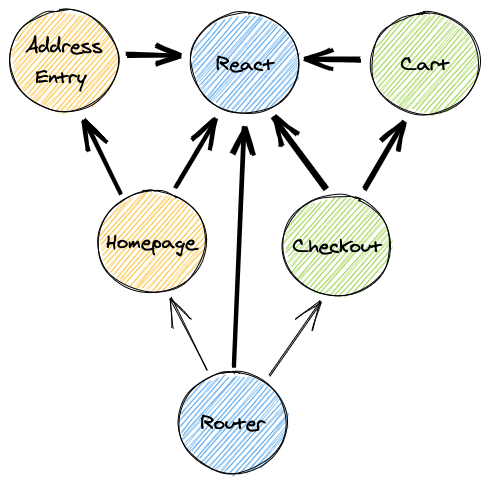

Figure 1. In this dependency graph of JavaScript files and components, thin lines indicate a dynamic import, while bold lines indicate a regular import. The colors illustrate one way that these files could be broken into separate bundles. The blue components have been identified as common to all entry points whereas yellow (left) and green (right) could be put in separate bundles.

Figure 1. In this dependency graph of JavaScript files and components, thin lines indicate a dynamic import, while bold lines indicate a regular import. The colors illustrate one way that these files could be broken into separate bundles. The blue components have been identified as common to all entry points whereas yellow (left) and green (right) could be put in separate bundles.

In the first version of UberEats.com, we tried to break our code into different bundles for each of the top-level pages to speed up load times. We also used a single, monolithic node_modules bundle for our project dependencies and created separate bundles for each of our top-level pages. One advantage of a monolithic node_modules bundle is that project dependencies don’t change as often as other parts of the codebase, making it easier for browsers to cache.

Unfortunately, code splitting didn’t yield significant performance benefits on the first version of UberEats.com. The data layer (Sagas, reducers, selectors, etc) constituted a large percentage of our overall application size and couldn’t be split up and loaded dynamically because we couldn’t statically determine what parts of the data layer were required for a given page. Even when the bundle size of the top-level pages was small, they still depended on roughly 300kb of data layer code, which put a lower bound on how much we could use smaller bundles to keep load times low and deliver a good user experience.

It was clear that significant changes were needed to the codebase to address the slow pace of development and performance issues.

UberEats.com’s new architecture

The original UberEats.com was written when server-side rendering with React was in its relative infancy, which necessitated a custom solution for core functions such as server-side rendering and data fetching. With these technologies now in a more mature state, we were hoping to shift to a more standardized solution that would remove some of the maintenance burdens from our team.

The new UberEats.com uses Fusion.js, a modern, open-source framework built by the Uber Web Platform team. Fusion.js augments the typical React/React-Router/Redux setup with a powerful plug-in architecture, server-side rendering support, and easy-to-use code splitting.

Under the hood, Fusion.js uses React Router version 4, a popular open-source routing library, which makes route-based code splitting easy. React Router uses a declarative approach that allows for new features to be added as routes on the appropriate page and lazily loads the feature-specific code when that route is navigated to. For example, we added the ability to place group orders post-launch by adding routes to the restaurant page which, when navigated to, would load the group order components, state management, and data fetching code. In order to fully split this code for our rewrite, however, we needed to architect our data layer differently than the original UberEats.com.

Data layer

The original version of UberEats.com had a plethora of Sagas and reducers which ultimately led to a bloated global state. Our performance and developer productivity goals required us to keep the global state lean. When re-architecting the data layer, we had a few different ideas on how to prevent history from repeating itself.

One way to keep the size of the global state small would be to lazily load reducers and constrain when Sagas can consume and dispatch actions. But once we mapped out the data requirements for each page, a simpler solution became apparent. Most of our application state was only relevant to the page it was accessed on, meaning we could rely on React’s local state instead of Redux’s global state. Rather than trying to scale Redux, we planned to drastically decrease our usage of it and shift state management from the global Redux store to the components that consumed it. This also aligned with the introduction of Hooks, a pattern that streamlined and encouraged local state management in React components.

In our new architecture, we still use Redux, but only for two uses: caching data that we don’t want to reload between page navigations (e.g., restaurants feed, restaurant menus) and to hydrate the client after a server render. Local state is used for all user interactions (e.g., selecting item customizations) and for data that we don’t want to cache between page navigations.

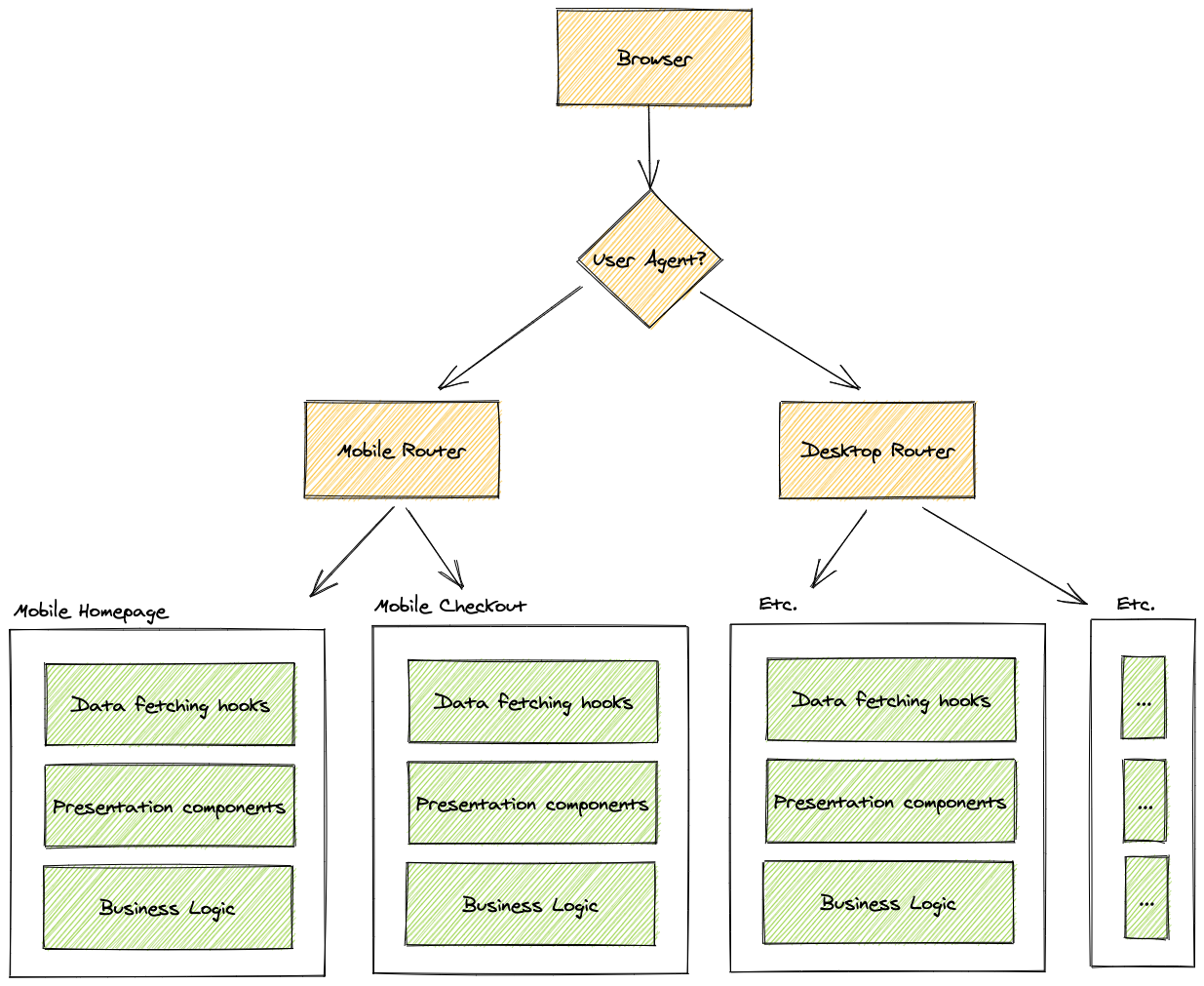

By using local state, we are able to co-locate the state management logic with the components that utilized it. Following this pattern makes code-splitting trivial–when we split a route from its main bundle, the system splits its associated data management logic along with it, as depicted in Figure 3, below:

Figure 2. The UberEats.com backend sends different bundles to users based on the user-agent header and page being accessed. We use a split entry point, where mobile and desktop devices receive entirely different top-level components. Bundle splitting within these components lets us isolate different features or pages as well as their respective data fetching and presentational needs.

Figure 2. The UberEats.com backend sends different bundles to users based on the user-agent header and page being accessed. We use a split entry point, where mobile and desktop devices receive entirely different top-level components. Bundle splitting within these components lets us isolate different features or pages as well as their respective data fetching and presentational needs.

The data layer handles fetching and providing data to components, but the components need a way to handle data that might not be loaded yet or that failed to load. To handle the different states data can be in we use a fairly simple abstraction, called Maybe.

type MaybeType<T> = {|

data: ?T,

error: ?Error,

hasLoaded: boolean,

isLoading: boolean,

|};

We can combine this Maybe with other Maybes to create a new Maybe or we can pass it into our MaybeLoaded component to conditionally render the data, as demonstrated below:

<MaybeLoaded

source={order}

loading={() => <Loading />}

error={err => <ErrorMessage error={err} />}

loaded={order => <OrderStatus order={order} />}

/>

Our data layer fetches information using an RPC-styled interface provided by Fusion.js. This interface matches our most common data fetching need of requesting an entity (e.g., a list of restaurants or a restaurant menu) from a single endpoint. Many new web applications at Uber use GraphQL and Apollo to request and combine data from multiple services. In the future, we may migrate to GraphQL and Apollo in order to simplify our data fetching code. We’re also excited about the possibility of swapping out MaybeLoaded once suspense for data fetching is stable, as this would keep in line with our architectural choice to rely on existing libraries and not custom code.

By keeping the fetching and management of data as close to the consuming components as possible, we were able to allow our data layer to easily be split between chunks. The resulting modular data layer was especially important since we were going to need to reuse the data layer between platform-specific components.

Two entry points

Typically, we can build a website that works on both mobile and desktop browsers by using media queries to show, hide, or move content. However, media queries fall short when the content on each platform is so different that it becomes difficult to maintain. In the original codebase, we used media queries along with platform code paths in components to address content differences on different platforms. This resulted in component trees with many conditional branches, making it difficult for engineers to trace through where a UI element was getting rendered.

At the start of the rewrite, we decided to have two separate entry points based on the platform. We did this to avoid the maintenance overhead that one entry point created in the original codebase and to ensure that each platform only loads code specific to it.

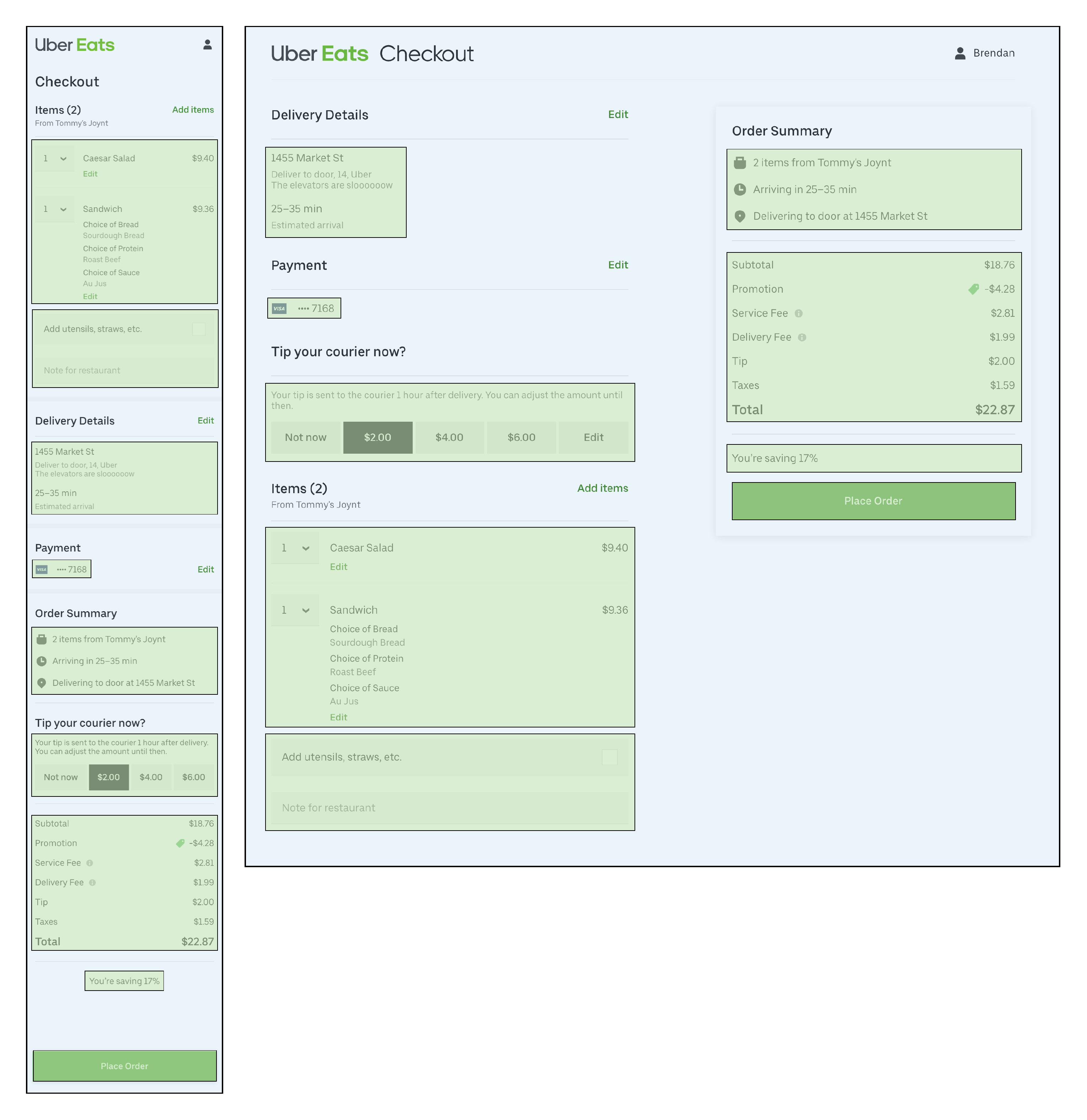

Now, mobile and desktop users only interact with the code required for their platform’s styling, simplifying the developer workflow, since they now only need to handle smaller components with fewer branches. Splitting the code also prevents styling regressions caused when a change is not tested on both platforms. While the platforms do share much of the same code, including elements like buttons, inputs, and list items, they usually diverge when it comes to layout code that arranges these shared components.

Figure 3. In these screenshots of the checkout screen on mobile devices (left) and desktop (right), we highlighted components shared between platforms in green.

Figure 3. In these screenshots of the checkout screen on mobile devices (left) and desktop (right), we highlighted components shared between platforms in green.

For example, implementing separate entry points notably simplified our address entry flow for UberEats.com. On the desktop version of the site, this appears as a dropdown typeahead located in the header. While on mobile, the flow is its own page. Being able to break out these two experiences reduced the complexity of the presentation components greatly but still allows us to share the business logic code used by both platforms.

Maintaining two entry points for mobile and desktop platforms allows UberEats.com to create components that are specifically tailored for a single platform, meaning they need to contain less code. Besides layout components, an example of a platform-specific component is the restaurant page header, which has a different design on desktop than mobile to take advantage of larger screens. The two entry points also let us generate chunks that contain only the code needed for the requesting platform. Beyond chunking code based on platform, we actually serve different code depending on the requesting device’s capabilities.

Different bundles for different browsers

Just as we had to rewrite UberEats.com for different devices, we needed to optimize it for different browsers, which presented another set of challenges and opportunities. JavaScript especially posed problems because it is a rapidly evolving language, with eight new language proposals expected to be published in 2020 alone. These features can help simplify code, reduce the surface area for bugs, or unlock new functionality. The previously discussed dynamic import syntax is one of the proposed features for 2020.

To actually use these new features we need browsers to support them and for people to use a supported browser. Unfortunately, browsers may have an incomplete implementation or not support a feature at all. On the rewritten UberEats.com, we use transforms and polyfills to take advantage of these new features without having to wait for all our users to upgrade to compatible browsers. Since transforms and polyfills add to the bundle size we only want to include them for browsers that don’t support the feature, and in order to do this, we serve browser-specific bundles.

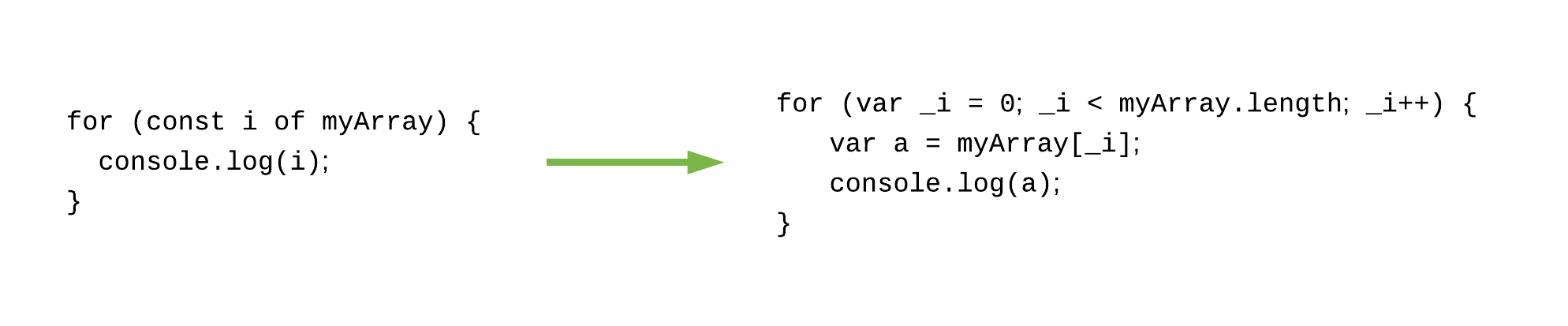

A transform takes a new feature and expresses it using syntax we know the browser will support. For example, we could express the newer for .. of iteration syntax as a regular for loop, which older browsers can understand:

Figure 4. In the UberEats.com rewrite, our transform simplifies a ‘for .. of’ to a ‘for’ so that all browsers can use this feature. This transform is provided by a Babel plugin.

Figure 4. In the UberEats.com rewrite, our transform simplifies a ‘for .. of’ to a ‘for’ so that all browsers can use this feature. This transform is provided by a Babel plugin.

Polyfills are also used to add support for new functionality. For example, an includes method was added to the JavaScript Array object in 2016. We could support this in older browsers by including a polyfill that extends the Array object’s prototype. A very simple, incomplete implementation of this functionality would be:

Array.prototype.includes = function(i) {

return this.indexOf(i) !== -1;

};

While these examples look straightforward, an unfortunate side effect of transforms and polyfills is that they can be very verbose. Properly capturing the semantics of a particular feature can require a lot of code. The polyfill for generator functions, for instance, is over 700 lines of code. The additional code required for transforms might start small but quickly become significant with repeated usage.

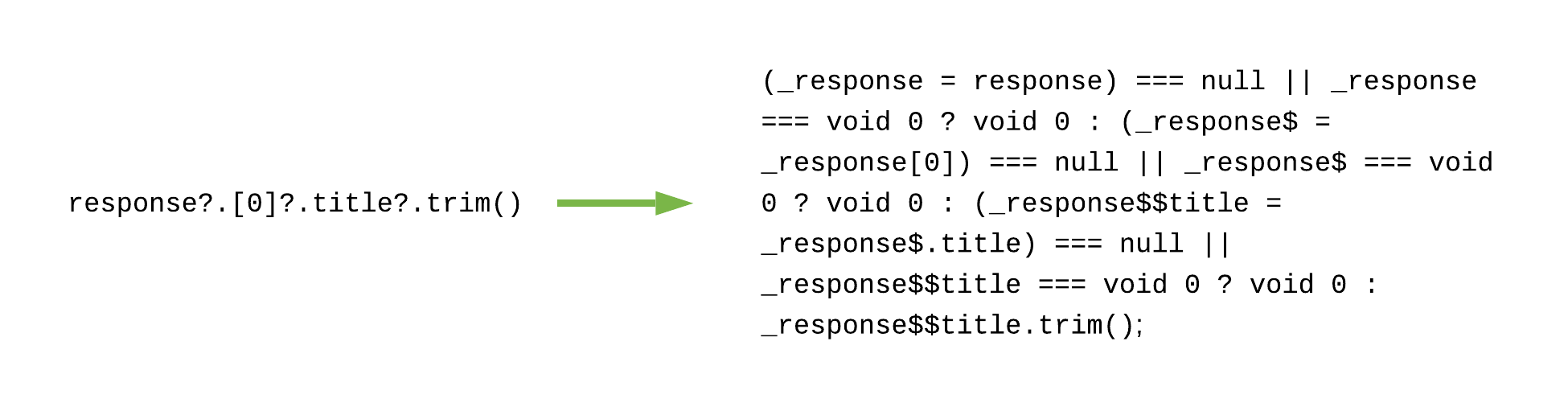

Figure 5. When we transform optional chaining to ES5 using a Babel plugin, the code becomes significantly more verbose. In this case, one line of code becomes seven, which increases the bundle size.

Figure 5. When we transform optional chaining to ES5 using a Babel plugin, the code becomes significantly more verbose. In this case, one line of code becomes seven, which increases the bundle size.

When a feature is widely supported by modern browsers, it can be difficult to justify the increase in bundle size for the sake of a small number of legacy browsers as this ends up degrading the experience for the majority of users. On the other hand, not introducing the transform means that some users may not be able to use the site at all.

Object destructuring is a good example of this issue, as the feature is well-supported by browsers with the exception of Internet Explorer. On the original UberEats.com, we had to make this tradeoff on a feature-by-feature basis to ensure we didn’t inflate the bundle size too much while continuing to support all browsers commonly used to visit the site.

For the new UberEats.com, we’re able to side-step this dilemma. At build time, Fusion uses babel-preset-env to create ‘legacy’ and ‘modern’ sets of bundles for our application. The modern bundle is intended for relatively modern browsers and can consequently operate with a much smaller number of babel transforms, while the legacy bundle allows us to keep serving the broadest audience possible by including more transforms and polyfills for older browsers. This approach results in a 15 percent decrease in bundle size for modern browsers and ensures that users on legacy browsers can still access the site.

Server-side rendering

In addition to improving browser accessibility, we also wanted to make sure that the rewritten UberEats.com would render its UI with minimal lag. To accomplish this, we chose to render site pages on the server, guaranteeing that all the necessary HTML and CSS would load without the need to execute any JavaScript. This was made easy through Fusion.js’ robust server-side rendering support. When running on the server, Fusion’s default behavior is to wait on RPC responses while rendering and write all required CSS directly to the page, ensuring an initial render of the content and a clean hydration process once the JavaScript finishes loading.

The decision to server-side render also has SEO implications. Some web crawlers will not properly execute JavaScript on pages, which might result in important content not being indexed. In this way, server-side rendering could allow UberEats.com to become more visible on search engines.

The performance implications for server-side rendering are mixed. During a server-side render, we typically have to wait for all API requests that fetch the data to finish before we can send the response (a web page) to the user. On the other hand, during a client-side render, the user has to wait for all the JavaScript to be downloaded and parsed before they can make any API requests. If the user’s browser takes a long time to parse JavaScript or their network connection is spotty, server-side rendering could result in a much better experience even if more time is spent waiting on the server.

On UberEats.com, we carefully choose what content we want to server-side render and what content we want to defer to be loaded on the client. As a general rule, we defer making API requests to the server when we expect the request to take a long time (over 500ms) so that the site loads faster. In this situation, we need to send down HTML that displays a loading state, wait for the JavaScript to load, make the API request, and then render the result.

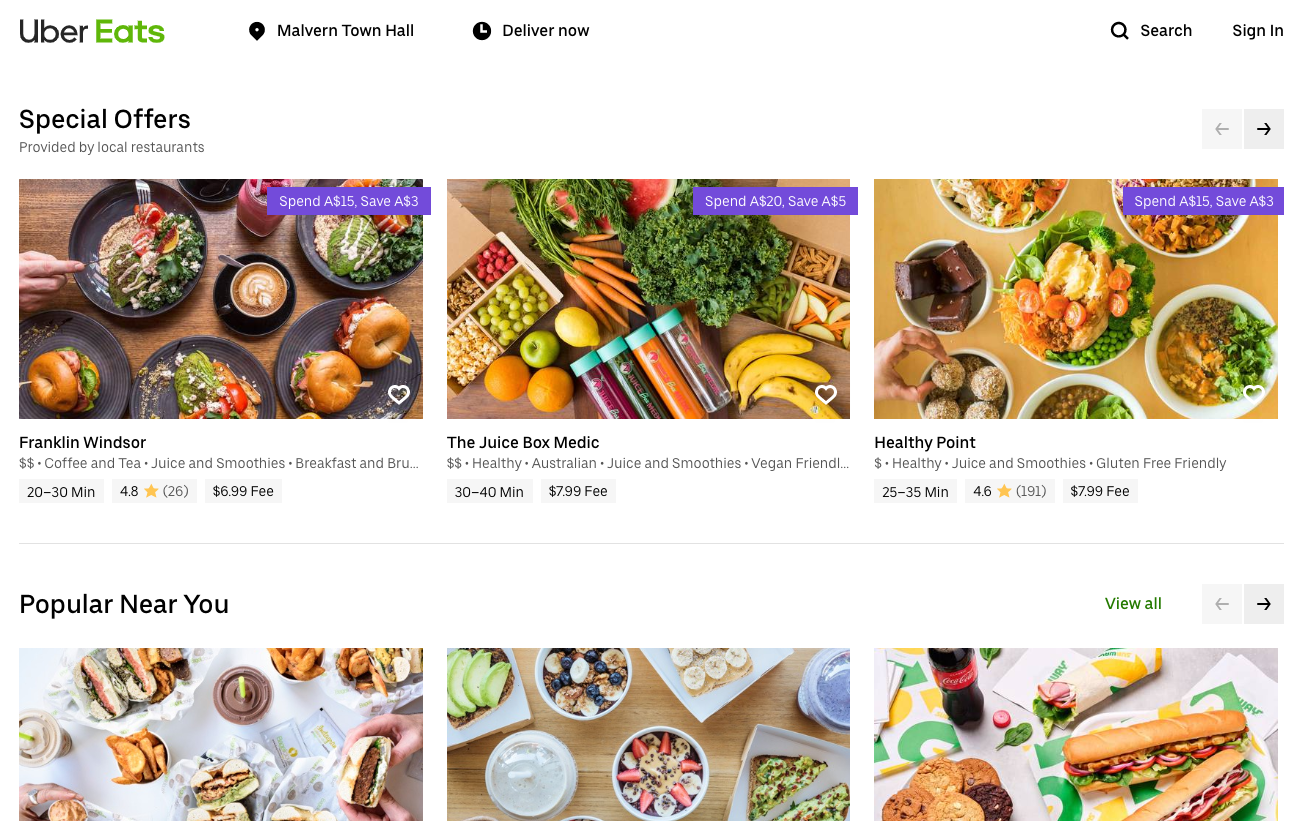

Figure 6. We adopted a hybrid approach for loading data on the Restaurants page.

Figure 6. We adopted a hybrid approach for loading data on the Restaurants page.

In other cases, a hybrid server-side and client-side rendering approach is appropriate. For example, loading the list of restaurants based on a user’s location and preferences is a slow API request so we cannot use server-side rendering. However, we want to display some restaurants to the user without having to wait for the JavaScript to load. To achieve this we have two API requests, one fast request to get popular restaurants that is included in the server-side render and then a second, slower request to get the remainder of restaurants that is requested from the client.

We decided there was no one-size-fits-all approach for server-side rendering. We hope to reduce all our API response times to what we consider an acceptable threshold, but in the meantime will continue to evaluate the decision to server-side render on a case-by-case basis.

Implementing continuous deployment

Once we rewrote UberEats.com, we quickly found that our approach to deploying builds also needed a makeover. Our original approach to deploying UberEats.com before rewrite was to tag a new release and run through our ‘sanity tests’, a comprehensive series of steps intended to test critical flows such as placing orders. We made the tests exhaustive to minimize the risk of a bad build. This meant testing various different types of orders on both mobile and desktop browsers.

If the build passed the tests, engineers would start a deployment and carefully monitor the build as it was being deployed for common errors such as uncaught exceptions. If an error was noticed by the engineer, they would roll back the build. While this usually prevented serious errors (such as those which broke core functionality like ordering food) from making it into production, it was time-intensive and slowed down developer velocity, preventing product engineers from working on new features. As part of the rewrite, we decided to automate the sanity testing and deployment process.

To make testing easier, we also converted the sanity tests into Puppeteer integration tests. Puppeteer provides a high-level API for controlling a headless Chrome browser, letting us simulate visiting and interacting with a test build of UberEats.com. The exhaustive nature of the sanity checklists made this process straightforward since each step (such as which page to visit or button to click) was documented in detail. For each integration test run, we created test delivery person, eater, and restaurant accounts in an isolated environment. We can use these for our integration tests without impacting other real users or even other tests that might have been running at the same time.

To streamline the deployment process we moved to a continuous deployment system. Continuous deployment, as the name suggests, is a process for automatically deploying changes once they have been landed and they pass our test suite (in this case, Puppeteer). The primary benefit to this approach is that changes get to production quickly, freeing engineers from the time-consuming process of sanity testing, starting, and monitoring deployments. The trade-off is that the team must ensure that our tests and alerts encompass all the possible failure scenarios. This inculcates a rigorous approach to monitoring, testing, and alerting within the team because there won’t necessarily be an engineer on hand monitoring the deployment.

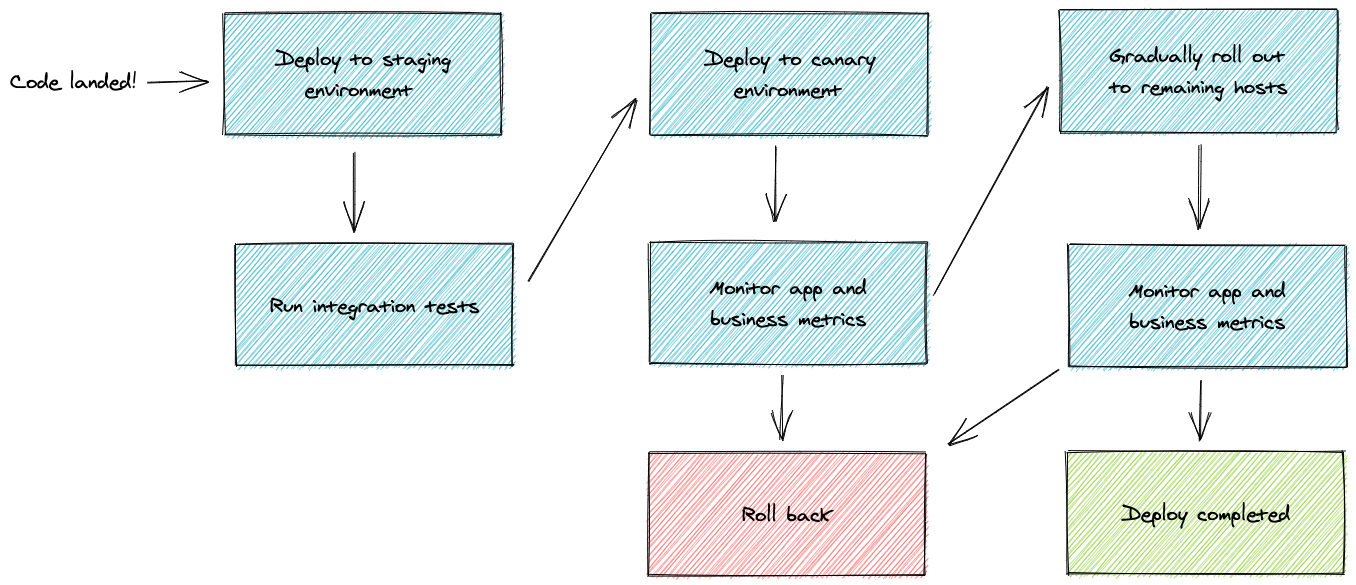

Figure 7. The deployment process for UberEats.com builds starts on the left with ‘code landed’ and follows the arrows until the application is entirely deployed or rolled back (based on business metrics).

Figure 7. The deployment process for UberEats.com builds starts on the left with ‘code landed’ and follows the arrows until the application is entirely deployed or rolled back (based on business metrics).

When a change is landed, our continuous deployment system deploys it to a staging environment, which is designed to closely resemble the production environment. The system runs desktop and mobile integration tests on core flows and other key site functionality. If the tests pass, we can be reasonably confident that nothing is horribly wrong with the build.

The next step is the canary environment, which contains a small subset of our production hosts. Our continuous deployment system observes how the build behaves in this environment for long enough to help ensure that the new build doesn’t impact our application health (such as through increasing the number of uncaught exceptions) or product metrics (for example, by decreasing the number of people who place food orders).

Once the build succeeds in the canary environment, our continuous deployment system gradually rolls it out to the rest of our servers over several hours. We intentionally stagger the deployment over a few hours so that we have ample opportunities to find and address any remaining issues.

If any of the deployment steps fail, the continuous deployment system rolls the build back and notifies the engineer who landed the change. When this occurs, the engineer involved manually pauses deployments and reverts the changes, since we try to avoid blocking the build pipeline for other engineers who may be trying to ship unrelated UberEats.com features.

While it requires an upfront investment in robust monitoring and integration testing, continuous deployment has saved us a significant amount of engineering time that can be re-invested in feature development and further architectural improvements.

The rewrite of UberEats.com allowed us to start with a clean slate and make architectural choices to maximize developer productivity and performance. By automating our build and release cycle, creating platform-specific presentational components, generating browser-specific bundles, and using more local than global state in our data layer, we significantly improved our developers’ ability to work quickly and effectively.

What we learned

While rewriting UberEats.com, we developed some best practices that can be applied to build an enduring system that is also easy for developers to work on:

Be mindful of abstractions

Fundamentally, code should be easy to understand. If an engineer needs to debug a feature, they should be able to follow the code path. This means they should know where prerequisite data originates and how a given code path interacts with the rest of the system.

A key lesson for us from our attempts at an in-place migration was that abstractions could harm readability and were difficult to undo once entrenched in a codebase. Abstractions should not exist for the sake of having an abstraction. They should capture a recurring pattern or concept within the codebase. We noticed that we sometimes needed to study a large number of use cases in order to fully understand the underlying concept we wanted to abstract. Creating an abstraction too early might lead to it missing important use cases, potentially necessitating a larger refactor than would’ve been necessary if we’d delayed introducing any abstraction in the first place. We applied this approach when creating separate mobile and desktop entry points. We were initially prepared to merge the two if an elegant abstraction emerged but ultimately felt that the repeated code was much easier to reason about.

Abstractions should also be easily debuggable. If an abstraction is being used to perform a certain function, such as loading data or waiting for an event, it should be clear whether the action succeeded or failed. We found that introspection can also be useful when tracing through a suspicious codepath.

It is often difficult to foresee how an abstraction might affect the future readability of a codebase, so we recommend approaching abstractions with skepticism until there is a strong need for one, such as repeated non-trivial code.

Avoid codebase fragmentation

There’s a tendency for codebases to become fragmented over time as engineers introduce different libraries, start migrations, or experiment with patterns. We certainly felt this was the case with our pre-rewrite codebase. Frequent contributors will become familiar and know how to navigate these obstacles, but this can be a huge problem for newer or infrequent contributors.

Feature development should be as simple as copying and modifying an existing file without having to worry about deprecated patterns of half-finished migrations. In practice, this limits the new patterns or migrations that we’re willing to attempt because any migration plan needs a viable plan for migrating the entire codebase and a realistic timeline. Automation can also help here as it lets us migrate large parts of the codebase programmatically.

Automate all the things

One of our goals with the rewrite of UberEats.com was to improve developer productivity. Engineering time is scarce and should be used wisely. Generally, tasks that can be automated with code-mods, static typing, tests, and lint rules should be.

Code reviews

To reduce time spent on code reviews, we ensured that any “stylistic” conventions in our codebase were enforced through ESLint, a JavaScript linter, and Prettier, an opinionated code formatter. We also wrote new rules to cover our own conventions and patterns which were too idiosyncratic to be supported by the available lint rules, including custom rules requiring that colors and margins conform to the Uber style guide.

Migrations

In addition to code reviews, migrations can also be automated with positive results. Migrations to new patterns can be challenging as they risk creating confusion or fragmentation within the codebase. We tried to mitigate this partially through the use of lint rules to ensure that new patterns were consistently used. For example, we added lint rules to prevent the introduction of new higher-order components as part of switching to hooks.

In other cases, we were able to automate the migration entirely because it was relatively easy to describe the necessary transformations to the abstract syntax tree in code by leveraging JSCodeshift to write and run these transformations. One example of this was the switch to optional chaining, an experimental JavaScript feature for making property accesses on a reference that might be undefined or null. Prior to optional chaining, projects would typically use a helper library such as Lodash or idx. We were able to automatically transform all our idx calls into optional chained calls, allowing us to take advantage of this new feature immediately.

Testing

Communication with product managers and designers can be time-consuming, as can testing specific parts of the user interface. We made use of Storybook, an open-source tool for rendering UI components in a sandbox environment, to isolate and document individual features. Each feature is rendered in all of its possible states in what is called a “story”. We developed automated tooling to capture API responses and save them as fixtures for stories. We could then send these stories to various stakeholders, who could validate their functionality without having to manually navigate to a feature, for example tracking an in-progress order.

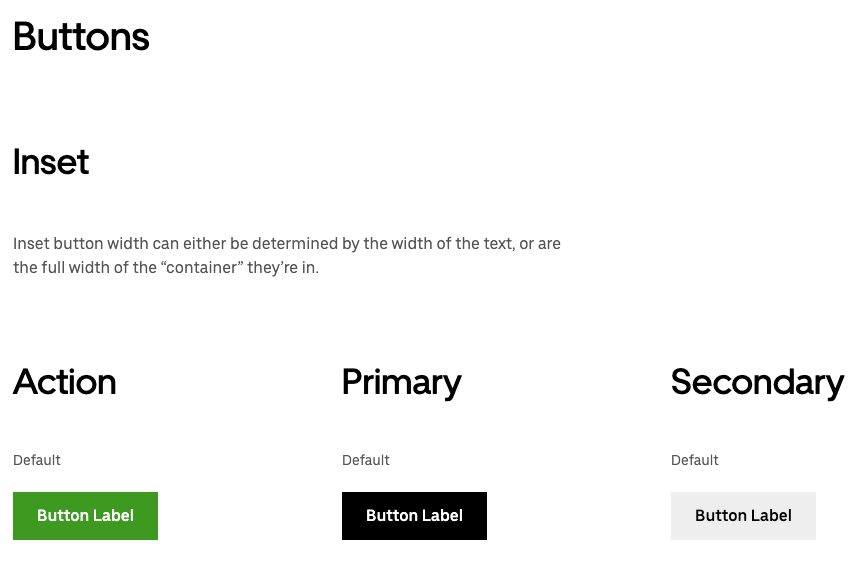

Figure 8. We built UberEats.com’s internal style guide using Storybook so developers would have a reference for visual elements such as buttons.

Figure 8. We built UberEats.com’s internal style guide using Storybook so developers would have a reference for visual elements such as buttons.

Automated testing was a key pillar in detecting regressions to our application without having to rely on time-consuming sanity testing prior to deployments.

Aside from the productivity benefits, going through the automation process forced us to think more deeply about what we were trying to accomplish, especially in the case of lint rules where we had to describe the undesirable patterns or intended behavior in code.

Through our UberEats.com rewrite, we learned that we can save engineers time if we focus on creating a readable codebase that’s well-tested and easy to extend. Making this architecture self-supporting through the use of automation to nudge engineers in the right direction can further remove the burden on engineers and help save even more time without compromising on correctness.

Moving forward

The re-architecture of UberEats.com was motivated by a desire to improve performance while making it easier for us to iterate on new product ideas. The rewrite not only met our performance and productivity goals, but it also exceeded them. For instance, the reduction in bundle size surpassed our original performance targets and afforded us time and resources that can be spent elsewhere.

The simplified codebase has also freed up engineering resources that can be dedicated to shipping more features for users. One recent feature that we’re particularly excited about is group ordering, where multiple people can share a single shopping cart. We hope this will take some of the stress out of ordering for multiple people. A stable and performant food ordering platform is just the beginning, as we continually experiment with new features to make the food ordering process more convenient.